Caption

This Almanac has been in the family since 1801 as I found it in a collection of family papers from NH and Maine.

Subhead

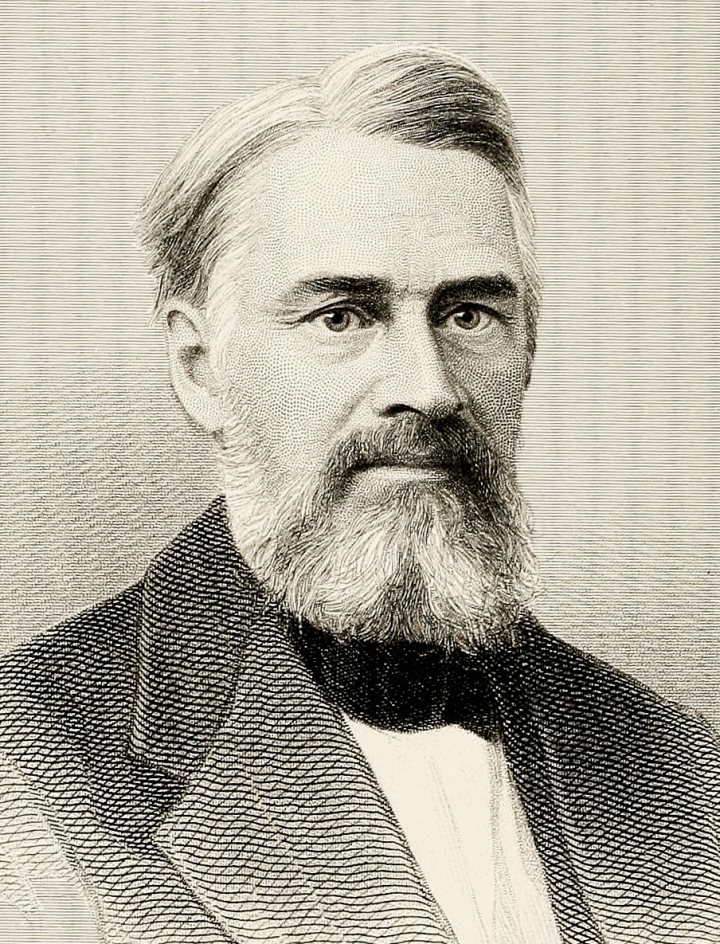

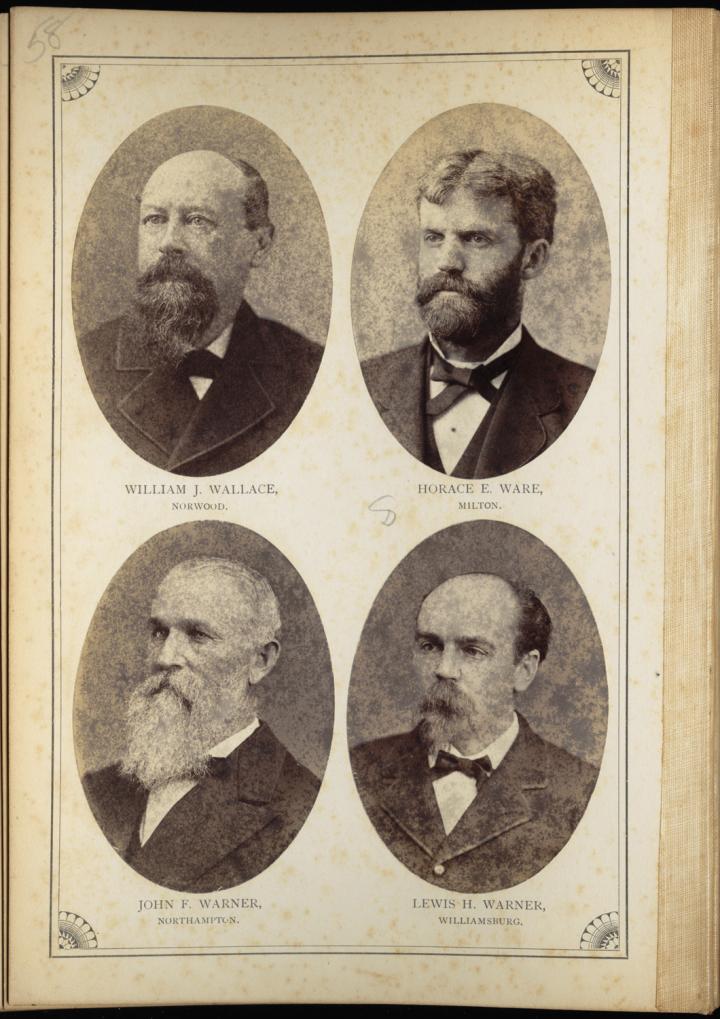

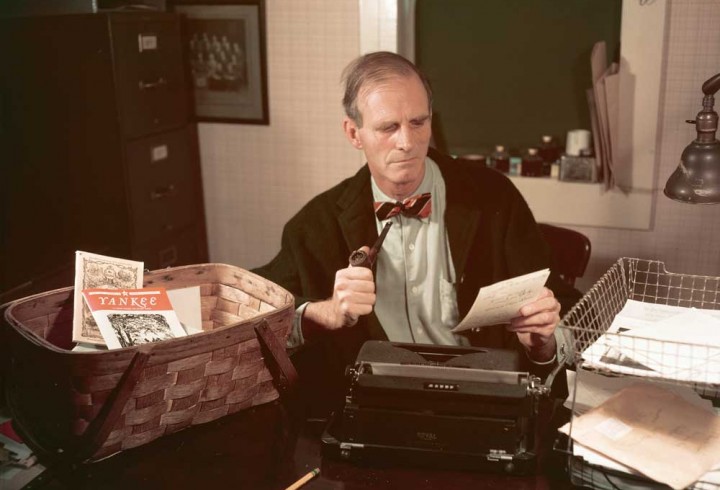

Learn about the 14 editors of The Old Farmer's Almanac—past and present.

No content available.

ADVERTISEMENT

Comments

Add a Comment

Also born on April 24th (1942) in Rhode Island, I have enjoyed the wit and wisdom of TOFA from time to time as did my dad. Grafton MA was the homestead with family truck garden of the Lupiens on my mom's side. Now retired to Arizona, we no longer can make pilgrimages to King Arthur in VT. Our best. JF