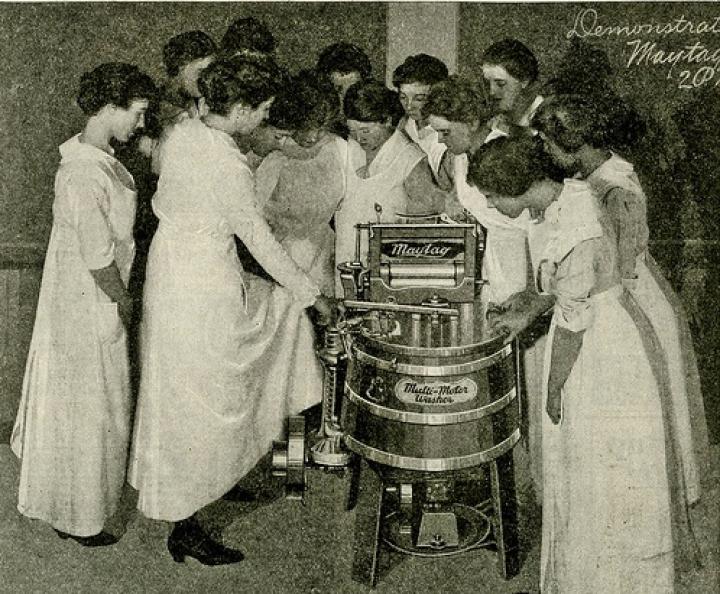

Signs of an emerging home ec for modern times

ADVERTISEMENT

As a retired home economics teacher--later family and consumer sciences, I saw many changes in the curriculum. We always tried to stay up with the times and teach relevant information that the students could use forever in their lifetimes. Many schools have had budget cuts leading to some useful classes being eliminated. So often I hear people talking about how students are not being taught "our life skills" as we called them. They are not learning etiquette, how to write thank you notes, basic banking skills, clothing care, nutrition, job skills, child care, etc. It is sort of like kids will have to learn lots of things on their own since schools can't and families may not be teaching them. Maybe one day the educational system will come back around and recognize it and restore the curriculum. I loved every aspect as a high school student and especially as a teacher for 38 years!

Not sure how worthwhile HomeEc is, as I was taught in a parochial school in the '60's, and we didn't have such classes. However, all my public school friends who did have them seemed to learn to hate cooking and sewing! I learned these skills after asking my mother to teach me, and loved doing them.

That being said, I learned VERY QUICKLY after I was married how to take care of a house, garden, budget, and later children. Unlike some women today, I considered my role as a housewife and mother (we preferred "Domestic Engineer" in those days) as very important and I took great pride in my skills. I now work out in the world for a paycheck, but those years of being the household manager are priceless. People on the jobsite are amazed at my ability to bake bread, make clothes, can food, etc. I think Margaret Boyles is correct, the wheel will turn full circle, eventually.

I think home ec does need to move out of the schools and into society in general as a pursuit worthy of serious policy, practice, and scholarship.

I always preferred the title of Domestic Goddess, and I still yearn for a new breed of Domestic Gods. Both genders need to tend to the productive (not just consumptive) activities of the home.

And that is exactly why we are where we are today. No respect for home, school, neighbors. It is an "instant society" when something brakes - get a new one not let me see if I can fix it. Apparently as can be seen by our society one parent needs to be home with the kids. They need to be taught respect. There is no God or discipline in school so the family must teach the basics of living in society. If they can - can we fix things????

Home economics is an important subject. They teach children their native language, transmit culture and values, and shape a child’s understanding of the world and of human relationships.

you're going to love each of the bell and whistles on the online slots free slot machine games

They should have a course titled, "first apartment". Many kids do not know the cost of basic food purchases, cooking, renting and heating. Nor do they know basic cleaning of clothes, themselves, or the apartment. Simple repairs such as a clogged sink or a running toilet were never taught at home. And the most wanted lesson never taught, how to respect your neighbors. They have to be reminded they do not live at home anymore. Include a lesson on budgets and what happens to credit.

Modern attitudes seem to get farther and farther from basics. You want to start at the top, with modern technology and equipment. The basics are still needed.. really. A child may not be taught at home, how to make a bed, comfortably and easily, without risking a back injury or why the sheets should be changed regularly. The importance of cleaning anything and everything or that not sanitizing a counter really can make your family sick. One of my home EC classes taught how to give a bed bath. That's something I've never learned anywhere else and it has been very useful knowledge, not fascinating, just useful. Like cursive writing, basic hygiene seems to be disappearing or there wouldn't be so many signs in bathrooms with instructions in hand washing.

Good points! I love the idea that home economics includes knowledge of how to give a bed bath, as well as the many forms of basic healthcare that help individuals and families avoid a trip to the doctor's office.

However, I'd suggest that "modern technology," at least in the form of online savvy, has become part of the basic skill set needed to navigate the modern world, learn, teach, solve problems, and collaborate.

From my perspective, home economics needs to expand way beyond the domain of schools and move into communities of place and communities of learning,in both physical and virtual environments.

I also think we need to infuse government policymaking with an understanding of the essential economic values of non-market (household)production of goods and services.

Interesting how these things have come full circle in my own lifetime! I took Home Ec as a youngster, watched the home arts become passe, and now am seeing a resurgence of home based skills and values. But I do not agree with the "unpaid" moniker. We homemakers are paid, not in cash, but in kind. A secure pleasant home is rewarding to the provider as well as to the family.

I couldn't agree more with your assertion that homemakers are richly rewarded for their work, Traci.

My concerns lie with the way in which our national accounting standards consider as "economic" only those activities that occur in markets (where consumers exchange cash for goods and services).

Shop at a supermarket, eat at a restaurant, pay someone to care for your children or adult parent, and the dollars you spend become part of the nation's Gross Domestic Product(GDP).

Grow a garden, prepare a meal,provide care for your children or elders, and the value of your labor disappears from any meaningful standard of measuring economic value. (Although the value of your raw materials, for which you pay cash, does count.)

Serious economists have calculated that the total value of the "household (non-market) economy," if we impute even a minimum dollar value to the labor involved, easily equals or surpasses the value of the market economy in advanced industrial democracies.

This matters a lot. What's invisible (the value of family caregiving, for example)isn't accounted for in government planning for health care,long-term care, and other social programs--remember, families' capacity for unpaid care is limited, and already stretched almost to the breaking point.

Unpaid family labor doesn't count towards social security benefits and other provisions for old age, dispriviliging (still mostly women)homemakers in their own elder years.

It's a complex matter. The value of nonmarket work needs a full accounting alongside our current standards of economic vitality, which don't even notice it.